Biden was executed in 2020? He’s been replaced by robotic clones? Does that mean that a robot beat Trump for the presidency of the United States?

Well, no, obviously a robotic clone Biden is not dealing with a cancer diagnosis, but US President Donald Trump reposted this conspiracy theory a few weeks ago.

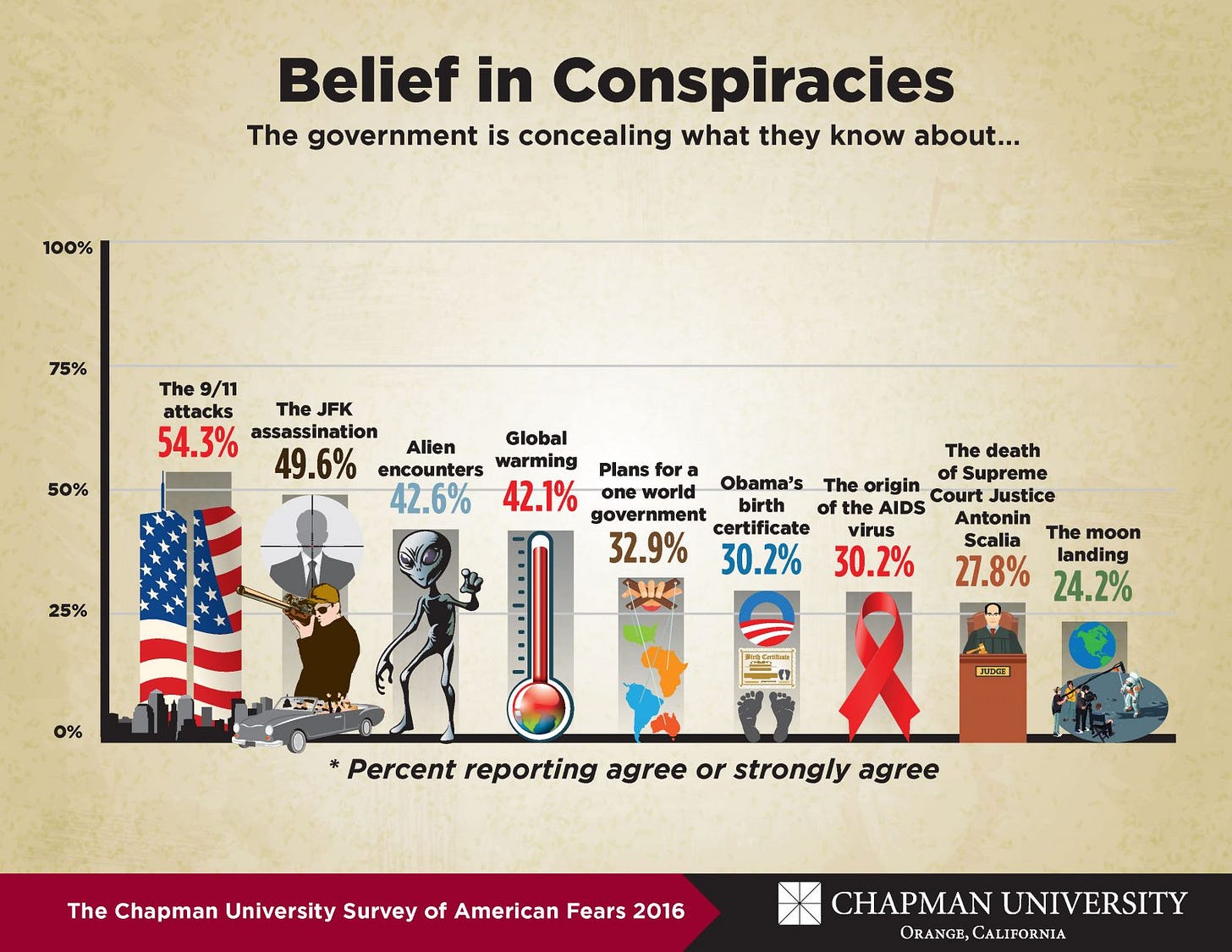

Many people around the world believe in conspiracy theories, with over a third of Americans thinking global warming is a hoax and more than half doubting the official account of President John F. Kennedy's assassination.

Another popular conspiracy theory that I apparently was out of the loop on concerns “chemtrails.” This theory claims that the white condensation trails left by aircraft are actually chemical or biological agents deliberately released under secret government programs. Despite scientific consensus debunking the theory, nearly one in five people globally believe it may be true.

And of course there is Qanon, which has emerged as a powerful and disturbing conspiracy movement in the United States. It revolves around baseless claims that a secret cabal of Satanic, child-abusing elites are trafficking children in order to harvest the hormone adrenochrome from their blood. And, what is worse, they are working against Donald Trump.

But conspiracy theories are not something new. They’ve been around for a long time. In ancient Rome, rumors spread that Emperor Nero had faked his suicide and would return to power. Some believed he was hiding in the East, plotting his comeback, while others thought he would rise from the dead. These fears were especially common among early Christians, who dreaded a return of Nero’s brutal persecutions.

These examples illustrate how conspiracy theories—ancient and modern—continue to capture the imagination and suspicions of people around the world. But what exactly are conspiracy theories, how do they get started, how do they spread and what needs do they fulfill for the believers?

What Is a Conspiracy Theory, Anyway?

Defining the Indefinable

Defining “conspiracy theory” can be a complex undertaking because of its ambiguity. The ambiguity originates from the various scholarly interpretations of conspiracy theories as some scholars regard conspiracy theories as unfalsifiable explanations of secret, malevolent plots, while other scholars see them as socially meaningful narratives that reflect broader cultural and political concerns. And, a definition and understanding of the concept of conspiracy theory rests on the level of analysis being undertaken.

However, a general working definition that seems to work for both interpretations revolves around theories that attempt to explain secret, often malevolent actions by powerful groups that are working against the interest of another group. These theories thrive in situations where mainstream or official explanations seem unable to adequately provide a trustworthy, emotionally satisfying and structured explanation to an event or series of events. These events are usually confusing, unsettling or threatening.

These conspiracy theories are difficult to falsify. One academic who was attempting to debunk the chemtrails conspiracy theory noted that the believer he was debating had a tall pile of documents and articles, both academic and popular that supported his belief that we are all being infected by chemical agents falling from above. And believers often accuse critics as being involved in the conspiracy itself.

So let’s take this definition from Wikipedia as our working definition of conspiracy theory: A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy, when other explanations are more probable. The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence.

Super Conspiracies and Political Exploitation

From the Shadows to the Spotlight

Before we go on to discuss how conspiracy theories spread, let’s modify our definition just a little. Political scientist Michael Barkun argues that today’s conspiracy theories tend to be different from those of the past. He calls today’s theories “super conspiracies” involving vast, global networks that control everything. According to him “super conspiracies” rely on three assumptions: there are no accidents, nothing is as it seems, and everything is connected. The results of these nefarious actions by some imagined elite players who are motivated by an overwhelming desire for power is to create a global society that is completely planned and controlled by them.

And these super conspiracies no longer operate in the dark on the fringes of society, but have now come into the daylight of mainstream beliefs thanks to the support of figures like Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Green and other politicians and right-wing cultural warriors in the United States.

Conspiracy theories are often created and utilized by populist political movements in the desire to increase political polarization on the road to gaining political, economic and cultural power. The creators need not actually believe in their theories. In fact, in some situations the creators have financial incentives in creating and spreading conspiracy theories like Alex Jones and his InfoWars website.

Social Media and the Mechanics of Spread

How the Internet Fuels the Fire

These days social media plays a major role in spreading and entrenching conspiracy theories. These platforms are like a fertile field that provides space where alternative belief systems can flourish. Communities of believers grow, and like weeds in a garden allow inhabitants to deepen their beliefs and set themselves apart from non-believers while proving to be almost impossible to eradicate.

Social media and online networks, forums and messaging apps like Telegram allow people to spread conspiracy theories by simply sharing or copy and pasting content. In those somewhat rare instances where non-believers are on one of these forums or apps and attempt to debunk misinformation, they are quickly shutdown by overwhelming numbers, and seem to actually reinforce the belief and commitment to a conspiracy theory.

Why People Believe – Psychology and Beyond

The Needs Behind the Beliefs

So why do people believe in conspiracy theories? We can look at two levels of analysis: psychological and social. In certain cases these two levels of analysis complement each other. However, as some anthropologists argue, there is often too much emphasis placed on psychological explanations.

At a psychological level of analysis, people may be attracted to conspiracy theories as a way to make sense of events in the world that at first glance seem complex, uncertain and even threatening. Belief may prove to be emotionally satisfying because a conspiracy theory leads the believer to find patterns in what seems to be unrelated events. This can give them a feeling of control and safety as the ambiguity and randomness that often appear to be integral aspects of modern life melt away under the glare of a theory that ties everything together even if the knots may be loose and fantastical. People who are looking for meaning in life or who distrust authority may be especially susceptible to following these theories.

Some research suggests that believers of conspiracy theories tend to have lower education and analytic skills, as well as a high need for closure. Believers may find a resolution for feelings of uncertainty, powerlessness, anger and frustration, although some psychologists believe that the resolution is only temporary.

Conspiracy as Community and Protest

From Fringe to Force: Power in Belief

Anthropologists and sociologists have often criticized psychological approaches as pathologizing behavior that can have positive individual and social functions. From an anthropological perspective conspiracy theories may provide believers with a sense of community and social connection as well as a framework for strengthening group bonds and identity, especially among marginalized groups.

One function of these theories is to push the blame for the hardships or failures of marginalized groups onto powerful out-groups. Believers in these theories often withdraw from mainstream political discourse and replace those social actions with membership in what have generally been considered fringe political groups, but which have now moved out of the shadows and entered into mainstream discourse as a form of resistance to elites who are usually the target of conspiracy theories as the architects of socially destabilizing events such as the Covid pandemic.

Traditionally analyses focused on marginalized individuals and groups who believe in conspiracy theories and bond together based on their beliefs. However, some anthropological research suggests that conspiracy theories should be looked at in the context of how they empower groups that are not necessarily marginalized and how they reflect local anxieties and social relations.

Thus these narratives may play a dynamic role in the mobilization of disaffected members of society so that they can act on their discontents against what they see as unfair cultural, economic, social and political elements that dominate public discourse and the organization of society.

Conspiracy theories are far more than laughable internet rumors or fringe beliefs. They are cultural expressions shaped by mistrust, uncertainty, and alienation—deeply rooted in both individual psychology and collective experience. Whether offering a sense of control, community, or resistance, they persist because they fulfill real emotional and social needs. Ignoring them—or simply mocking their believers—misses the point. To understand why these narratives thrive, we must look at the systems and structures that leave people feeling powerless and confused in the first place. Only then can we begin to counter their appeal not just with facts, but with empathy and societal change.